Primordial black hole as a source of new physics detection

I’m going to start a plan from today.

I’ll irregularly write blogs to introduce interesting paper I have noticed and read. I’m not assuming the readers are expert, so I may write some things that look explicit/naive to some senior people.

The papers may not be very new and up-to-date.

Today I’ll introduce 2 papers from the UMD theory group in the past 2 years.

Detecting Axion-Like Particles with Primordial Black Holes

Light in the Shadows: Primordial Black Holes Making Dark Matter Shine

Can current-existing primordial black holes (PBH) help us detecting new particles? These 2 papers show a great example.

The first paper is very straightforward: PBH can emit particles, and thus can become a natural source of particle factory. As long as those produced particles can be detected, it’s promising for new physics discovery or exclusion.

This paper uses axion-like particle (ALP) as an example. Here we assume that the ALP decays into a pair of photons. If ALP is produced from PBH and decays into photon pair before arriving to the earth, it’s promising to be detected by future experiments like e-ASTROGRAM or AMEGO.

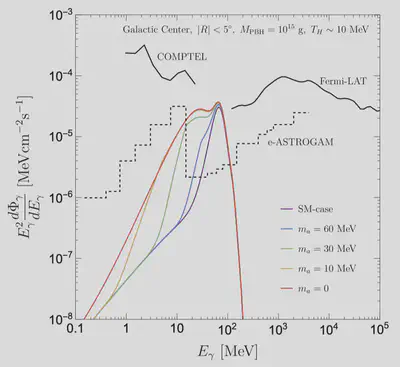

Can the Standard Model (SM) produce similar signal? Yes. The PBH can directly radiate out photons. However, ALP can distort the photon spectrum, and still lead to new physics discovery, shown in the following plot.

It’s easy to see that ALP can change the shape of the detected photon spectrum. After performing statistical analysis to quantify how large the deviation is between the ALP-modified spectrum and the pure SM result, we can probe ALP from the photon spectrum distortion.

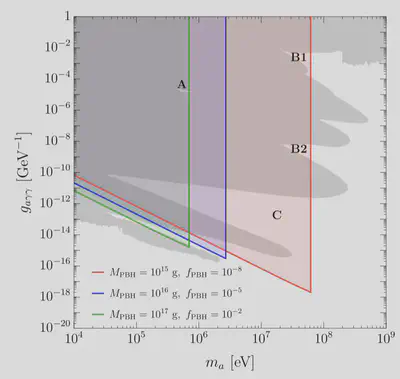

Results shown in the next plot.

The shaded region is the projected reach: assuming the black hole has the corresponding mass (e.g. red color means PBH haves a mass of $10^{15}$ g.), ALP with such a mass and coupling is projected to be discovered. If we have such a PBH but still not discoverd, then this parameter space is excluded.

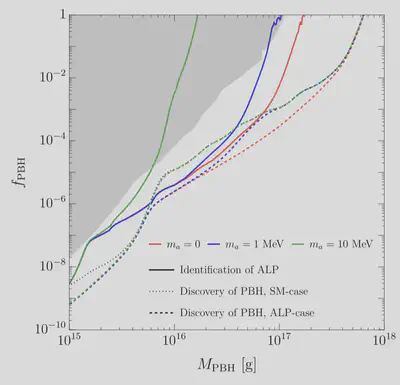

Or we can do it oppositely: if we want to probe a specific parameter space, what is the required PBH mass?

The answer is given in the next plot: e.g. the blue curve means only PBH with parameters located in the upper region is capable of producing enough 1 MeV ALPs to be discovered.

Using the similar way, if we go one step more, PBH can do the following for us:

Sometimes dark matter annihilation nowadays is weak, and it’s very difficult to find dark matter from indirect detection (which captures the annihilation product of dark matter). For example, asymmetric dark matter has a low current abundance of the anti-particle of the dark matter. The dark matter cannot find is annihilation partner, and thus indirect detection is difficult.

PBH can make it up: lack of annihilation partner? I’ll produce for you.

That’s what the second paper is doing.

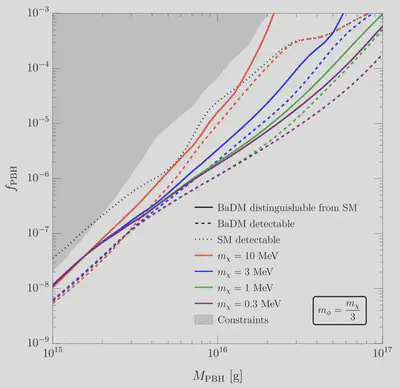

This paper has 2 example models. Here I would just mention one of them: the boosted anti-dark matter (BaDM). The result plot is the following:

Some key points:

- How is the detectable particle mass range determined? The answer is PBH temperature, which behaves like $1/M_{\rm PBH}$. A lighter PBH leads to a higher temperature, making it easier to radiate new particles. That’s why the parameter to the upper-’left’ region of the curve in the above plot is capable.

- Too light PBH evaporate too early and cannot survive until today, so there should be a lower limit on the PBH mass. That means we cannot detect particles with arbitrarily high mass.

- What’s the advantage of PBH versus accelerators? The PBH produces particles with gravitational effects rather than particle couplings. So BSM particles can be strongly produced even if the coupling is weak. Producing a weakly-coupled particles, on the contrary, is difficult in accelerators.

And, I love the introduction of the second paper!